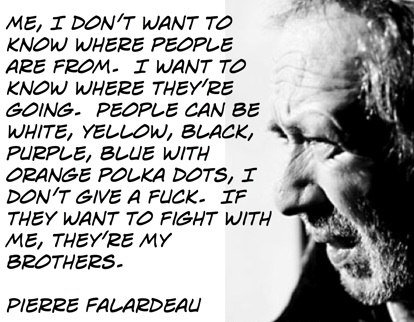

Pierre Falardeau: The Original Angry French Guy

The best interview of Pierre Falardeau I ever saw was the only one I ever heard him give in English. In English Falardeau couldn’t pull the rancid foul-mouthed chain-smoking schtick that had made him such a polarizing and familiar face on TV. In English he was just a soft-spoken filmaker talking about his art.

To most people, however, the director of Elvis Gratton, Octobre, Le Party, Le Steak and 15 Février 1837 will always be the bitter and angry separatist ranting about the Molsons, Trudeau and Big Federalist Media, waving his cigarette menacingly. Pierre Falardeau died yesterday. Not from lung cancer, in case you were wondering.

Pierre Falardeau’s character served him well. It made him a celebrity. A media personality. It didn’t matter if people liked him of not, he could deliver the ratings. Once it even got him a seat on Bouillon de Culture, the French TV show about Haute Culture where a dozen parisian luminaries with broom handles up their asses talk about Alain Finkelkraut’s latest essay for four and a half hours. Falardeau slouched on his chair, smoked on the set and cranked the joual to blasphemous. The French loved him.

Falardeau constantly had to sell himself because he wouldn’t sell out. He refused to shoot commercials to make a living. Since it’s just about impossible to raise the money to make a movie anywhere outside Hollywood without governement financing Falardeau had to go on TV and put on a show every so often to remind his fans that he was waiting on a check from Telefilm Canada, the governement agency that funds canadian movies.

Without the public pressure from his fans the militant filmaker knew his scenarios would have been killed one after another until he would have broken down and agreed to make films about « the migration of Canadian geese and the existential angst of Outremont’s middle aged. »

He wasn’t faking. He really was angry. He had to fight for every foot of film he ever got. Guerrilla warfare. He had to set the original script of 15 Février 1837, his movie about the Patriot Rebellion, in Poland to get it past a first round of bureaucrats.

Ultimatly, though, it got old. Falardeau got stuck in his character: a drooling separatist bogey man consumed by anger. A defeated man who would never live his dream of an independent Québec.

That’s why it was so refreshing to discover the other Falardeau in that English interview. The anthropologist. The scholar of imperialism and colonisation. The man who’s ultimate struggle was not about some administratively independent state for Québec but giving the Québécois the opportunity to make and watch their own stories on the big screen before they came to believe, like Elvis Gratton, that American stories are the only stories in the world.

–But you keep bitting the hand that feeds you! said the reporter in the English interview. Why should canadian taxpayers give you any money at all?

-Because I’m the only filmmaker in Canada who’s movie have ever made a profit, quitely answered Falardeau. I don’t cost money, I make money.

Things have changed since that interview. This summer Québec movies made 18% of the box office revenue in the province. The top grossing film of the entire summer, beating Harry Potter, Tansformers and G.I. Joe, was De Père en Flic, a Québec movie. There are very few countries in the Western world where domestic movies have that big a share of the market. Canadian films count for less than 2% of tickets sold in English Canada.

But before they could start building a man had to come to claim the land. He had to cut down the trees and scorch the earth. He had to fight off the bears and squatters. He had to make sure the bankers money would be used to build a railroad. It was tough work. Not for your average film school grad.

The only reason there is a Québec film industry at all is because Pierre Falardeau proved that moviegoers would come out and pay to see a Québec movie at the multiplex. Slapstic comedies, documentaries and historical dramas.

Pierre Falardeau made Québec’s commercial film industry possible. And he did it without selling out. Respect.