The Glorious Bilingual Montreal of the 1940’s

Did French and English Montrealers ever live in the same city?

Was there ever a Golden Age when French-speakers looking west and English-speakers looking east had a converging point of view on the history and future of Montreal?

Consider this:

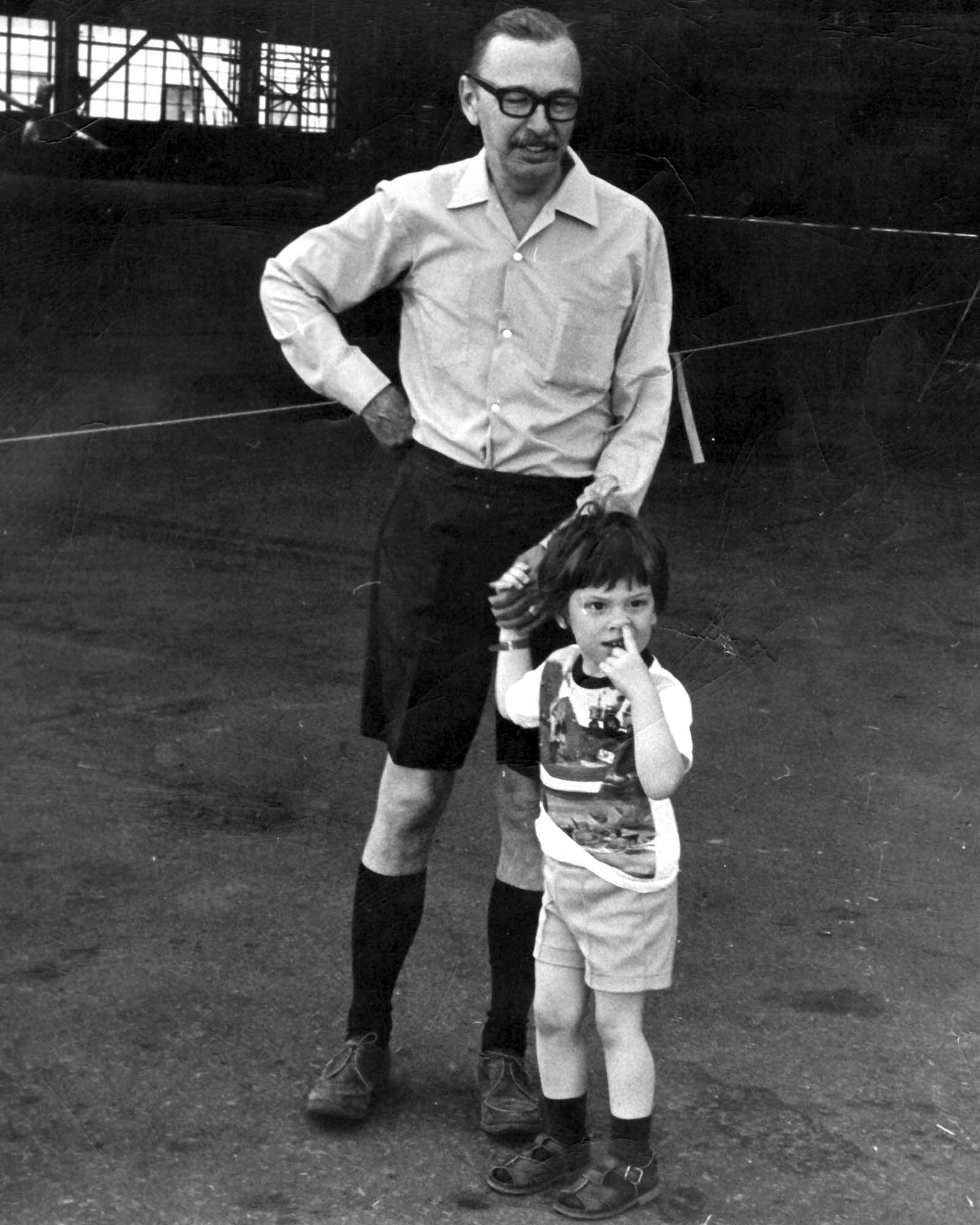

In 1941 the National Film Board of Canada hired my grand-father, Vincent Paquette, as the agency’s first French-Canadian filmmaker and head the embryonic « French Unit »

It is important to emphasize that, as his name does not indicate, Vincent Paquette was as bicultural a Canadian as this country has ever produced. His Franco-Catholic father, Albéric Paquette, met his mother, Eva May Hathaway, the daughter of a Loyalist minister, in Toronto. The couple raised their children in Montreal and in the still very English Sherbrooke, Québec of the 1920’s where my grand-father grew up thinking of himself as an English kid.

« In Sherbrooke I went to French primary school », he wrote – in French – in his unfinished memoirs. « Since my mother tongue was English, since English was the usual language at home and in most of the streets, it made for a rather difficult start. »

He went on to complete all of his studies in French, studying in Montreal’s Collège Saint-Laurent with such Québec icons as Félix Leclerc.

That said, it is needless to say that his English background had something to do with the NFB’s decision to put a 26 year old with no filmmaking experience in charge of the Board’s first French filmmaking department, a department originally created to translate propaganda films during the Second World War.

In 1942 my grand-father set off to direct a film on the celebrations commemorating the tercentenary of Montreal, which would become the first movie ever shot – as opposed to translated – in Canada’s two official languages.

Even with his Upper Canadian roots counterbalancing his Franco-Catholic education, it quickly became clear that my grand-father’s understanding of Montreal was not what the head office had in mind. Right from the start, serious incompatibility between the English and the French perspectives became apparent and on at least two occasions proper Anglophones were hired to finish the project.

In the end my grand-father would get credits for both versions of the film, but while his cut was used for the French version, the English version followed the storyboard from upstairs.

NFB historian Pierre Véronneau writes about differences between the French and English versions in his PhD. thesis: « It would be quite simple to show that the English version trivializes certain actions or certain situations perceived as important or heroic by the Québécois. »

The French version was anchored around four themes: modern Montreal, French Montreal, Montreal at war and religious Montreal. Véronneau notes that the modern and religious themes occupy more or less equal time in the French version, and that the latter is all but evacuated from the English versions.

The religious images are quite frankly astonishing for someone born after the Quiet Revolution. It is near impossible today to imagine the bishop taking the vows of hundreds of new priests in the streets of downtown Montreal, surrounded by thousands of nuns in black and white and clerics in red and gold. The protestant businessmen of the Sun Life building might have been the future of Montreal, but the Catholics had cooler hats

On the war effort, the commentary of the French version went: « Today, grandiose realization of Paul Chomedey de Maisonneuve’s dream, Montreal put all of it’s energy and all of it’s resources to the service of peace in plenitude. Concordia Salus. » Véronneau wonders aloud: « Can we see here a covert position? A diaphanous echo to the French-Canadian resistance to any direct participation to the war? »

Athough the metaphore is not quite politically correct, I do note with much relief that my Grand-father had not succumbed to the fascist muses: « Paquette makes the Iroquois of yesterday the German of today, and the determination of the Québécois to combat him, eternal. »

On the question of language, « The English version emphasizes the bilingual character of the city while the French version underlines it’s French character. » Hum… sounds familiar….

Vincent Paquette made a few other films for the NFB before moving on to a career in advertising and the federal public service. Although he never was known as a nationalist, Eva May Hathaway’s son voted YES in the 1980 referendum on Québec sovereignty.